Harvard stem cell scientists studying the effect of nitric oxide on liver growth and regeneration appear to have serendipitously discovered a markedly improved treatment for liver damage caused by acetaminophen toxicity—the cause of half the U.S. hospital visits related to acute liver failure.

Harvard stem cell scientists studying the effect of nitric oxide on liver growth and regeneration appear to have serendipitously discovered a markedly improved treatment for liver damage caused by acetaminophen toxicity—the cause of half the U.S. hospital visits related to acute liver failure.

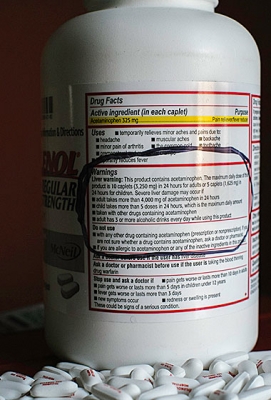

The human liver can safely process up to 4 grams (8 pills) of acetaminophen—best known as Tylenol®—in a 24-hour period, but going over that amount risks poisoning or killing liver cells. Accidental acetaminophen overdoses commonly occur—and with fatal consequences for hundreds of people each year—when those who feel sick and are unaware of the dangers posed by the over-the-counter pain and fever reducer exceed the safe dosage.

In the journal Cell Reports, the researchers described how nitric oxide—which is commonly used to relax cardiac blood vessels in heart disease patients—enhances liver growth and regeneration independently of its effect on blood vessels. The research team also showed, using zebrafish and mice, how manipulating these pathways with drugs could help in the clinic, specifically by improving treatment of toxic liver injury caused by acetaminophen overdose.

The only federally approved treatment for acetaminophen toxicity, N-acetylcysteine (NAC), is most effective if a patient seeks medical help within 8 to 12 hours of overdose. Unfortunately, most overdose-specific symptoms, such as confusion and intestinal bleeding, don’t occur until the liver injury is critical.

“We tried to model that in our studies where we gave fish Tylenol first, waited 18 hours, and gave them a new nitric oxide-based drug combined with the clinically approved drug,” said study co-senior author Wolfram Goessling, MD, PhD. “These drugs worked together to improve liver injury even when out of the previously established therapeutic window and so we think there’s significant potential for clinical application.”

Goessling and his research associates happened across the nitric oxide-liver injury connection while investigating the signaling pathways that are important for liver development. His lab, which he shares with other study co-senior author Trista North, PhD, screened thousands of known drugs on zebrafish embryos to see which produced a bigger or smaller liver. The compounds with the most dramatic effect were a family of drugs that affect nitric oxide and nitric oxide signaling.

Andrew Cox, PhD, a Goessling postdoctoral fellow, conducted a series of experiments to show that nitric oxide enhances liver formation during zebrafish organ development and that blocking nitric oxide leads to smaller, less-developed livers. Further investigation found that nitric oxide works through separate pathways in the liver than in the blood vessels, where its ability to regulate blood flow has been well established.

“During these experiments we found a recently recognized pathway, called protein nitrosylation, where the activity of proteins gets changed by nitric oxide,” Goessling said. “We think that’s the basic principle behind how it works in liver development.”

The Goessling and North lab members found that it’s possible to enhance liver growth and regeneration by disrupting the nitrosylation pathway so that nitric oxide is better able to change proteins in liver. They found a nitrosylation enhancer currently used in clinical trials for other purposes and began testing it in different clinical models of diseases, such as that of Tylenol overdose, where it proved successful.

“This potential drug doesn’t only work in fish,” Goessling said. “We did use mouse models to show that this might have relevance to human disease.”

If the nitrosylation drug for liver toxicity reaches clinical trials, it would join a handful of other drugs developed from zebrafish research that originated from Harvard Stem Cell Institute labs. Last year, a compound discovered by North and Goessling while being postdoctoral fellows in the lab of Leonard Zon, MD, was found to expand cord blood during hematopoietic stem cell transplants in a Phase 1b clinical trial. Another drug for melanoma, also discovered in the Zon lab, reached the federal Food and Drug Administration approval process in 2011.

Wolfram Goessling, MD, PhD, is a Harvard Stem Cell Institute Principal Faculty member, and a Harvard Medical School Assistant Professor of Medicine and of Health Sciences and Technology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute. Trista North, PhD, is also a Harvard Stem Cell Institute Principal Faculty member and a Harvard Medical School Assistant Professor of Pathology at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. Leonard Zon, MD, is the chair of the Harvard Stem Cell Institute Executive Committee, and founder of the Stem Cell Program at Boston Children’s Hospital.

This research was funded by a Harvard Stem Cell Institute Junior Faculty Grant, a Public Health Service Grant, the Pew Charitable Trusts, and an American Liver Foundation Postdoctoral Research Fellowship Award.

Cited: S-Nitrosothiol Signaling Regulates Liver Development and Improves Outcome following Toxic Liver Injury. Cell Reports. January 16, 2014