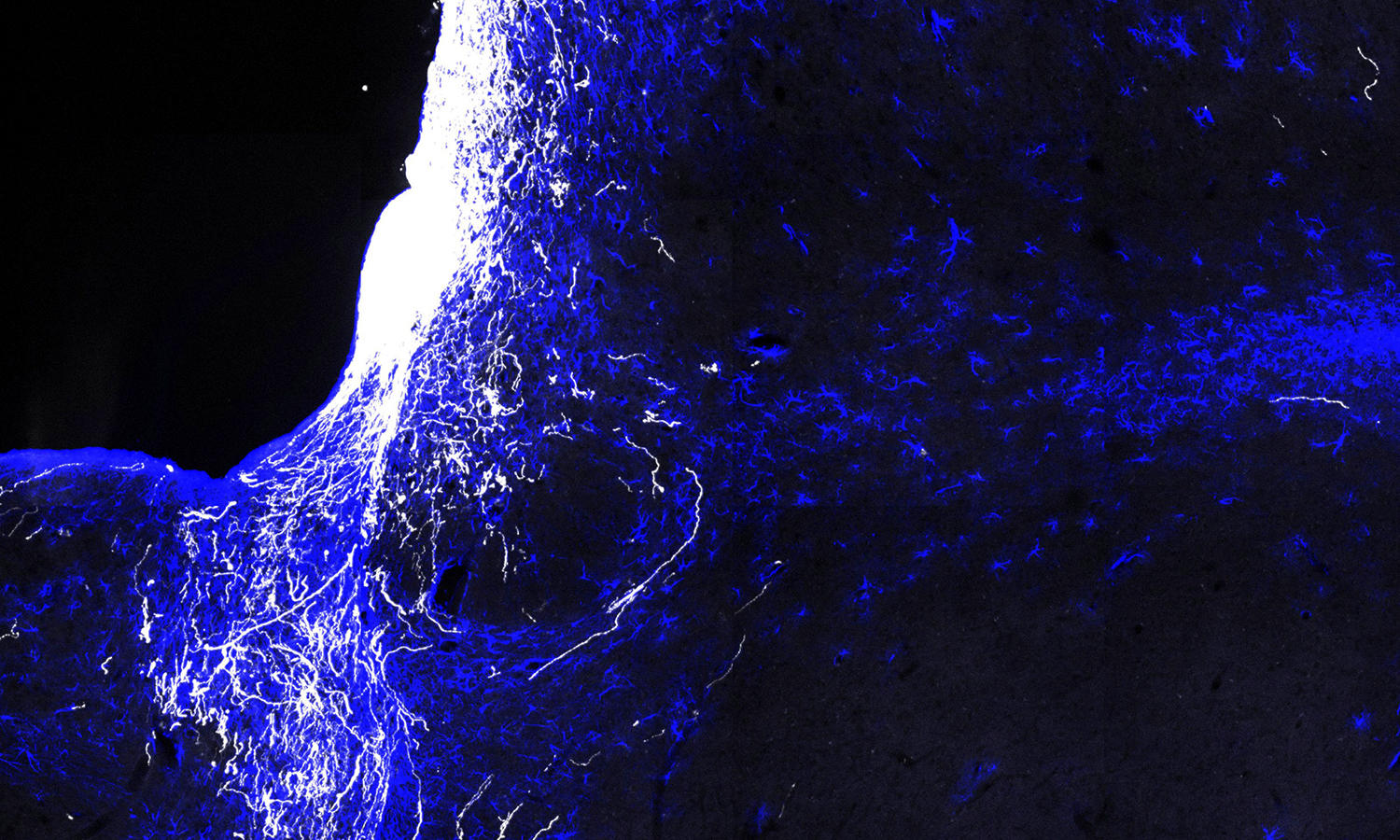

Despite scar tissue (blue), axons were able to regenerate (white) after axon injury. HSCI researchers show axons form functional synaptic connections with their target, but unexpectedly, exhibit conduction defect due to lack of myelination. Combining regeneration with pharmacological blockage of potassium channels effectively rescues the conduction defect and results in behavioral function restoration. Photo courtesy of Fengfeng Bei.

Channel blocker drug, added to regenerative factors, is key

Harvard Stem Cell Institute (HSCI) researchers at Boston Children’s Hospital suggests the possibility of restoring at least some visual function in people blinded by optic nerve damage from glaucoma, estimated to affect more than 4 million Americans, or from trauma.

As reported online January 14 by the journal Cell, the scientists restored vision in mice with optic nerve injury by using gene therapy to get the nerves to regenerate and — the crucial step — adding a channel-blocking drug to help the nerves conduct impulses from the eye to the brain. In the future, they believe, the same effect could be achieved with drugs alone.

In the study, previously blind mice turned their heads to follow patterns of moving bars after given the treatment, say co-senior investigators Zhigang He, PhD, and Michela Fagiolini, PhD, of the Department of Neurology and F.M. Kirby Neurobiology Center at Boston Children’s. The technicians doing the tests did not know which mice had been treated.

“By making the bars thinner and thinner, we found that the animals could not only see, but they improved significantly in how well they could see,” says Fagiolini.

While other teams, including one at Boston Children’s, have restored partial vision in mice, they relied on genetic techniques that can only be done in a lab. Generally, their methods involved deleting or blocking tumor suppressor genes, which encourages regeneration but could also promote cancer. The new study is the first to restore vision with an approach that could realistically be used in the clinic, and that does not interfere with tumor suppressor genes.

Getting nerves to conduct

The key advance in restoring vision was getting the regenerated nerve fibers (axons) to not only form working connections with brain cells, but also to carry impulses (action potentials) all the way from the eye to the brain. The challenge was that the fibers regrow without the insulating sheath known as myelin, which helps propagate nerve signals over long distances.

“We found that the regenerated axons are not myelinated and have very poor conduction — the travel speed is not high enough to support vision,” says He, a Principal Faculty member at HSCI. “We needed some way to overcome this issue.”

Turning to the medical literature, they learned that a potassium channel blocker, 4-aminopyridine (4-AP), helps strengthen nerve signals when myelin is absent. The drug is marketed as AMPYRA for multiple sclerosis, which also involves a loss of myelin. When they added it, the signals were able to go the distance.

A paradigm for treating glaucoma and optic nerve injury

While the study used a gene therapy virus called AAV to deliver the growth factors that trigger regeneration (osteopontin, insulin-like growth factor 1 and ciliary neurotrophic factor), He and Fagiolini are testing whether injecting a “cocktail” of growth factor proteins directly into the eye could be equally effective.

“We’re trying to better understand the mechanisms and how often the proteins would have to be injected,” says He. “The gene therapy virus we used is approved for clinical study in eye disease, but a medication would be even better.”

With regeneration kick-started, 4-AP or a similar drug could then be given systemically to maintain nerve conduction. Because 4-AP has potential side effects including seizures if given chronically, He and Fagiolini have begun testing derivatives (not yet FDA-approved) that are potentially safer for long-term use.

The researchers are further testing the mice to better understand the extent of visual recovery and whether their approach might get myelin to regrow over time.

“The drugs might need to be paired with visual training to facilitate recovery,” says Fagiolini. “But now we have a paradigm to push forward.”